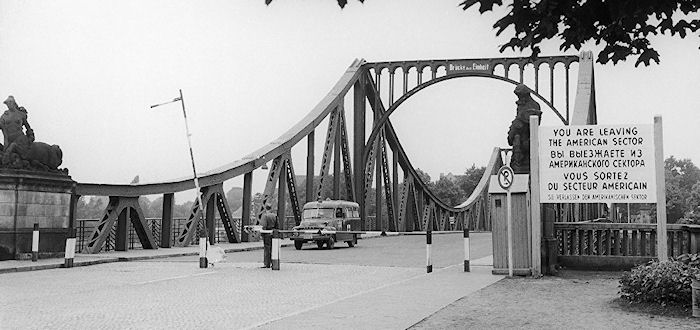

On February 10, 1962, two men stepped on to opposite ends of the Glienicke Bridge in Berlin.

Francis Gary Powers—a prisoner of the Russians since 1960— faced westward. Rudolf Abel—captured by the FBI in 1957—faced eastward. Both men had been captured while performing daring intelligence missions. When the signal was given, Powers and Abel began to cross the bridge. They passed in the middle of the bridge, with barely a nod. They were headed home.

Spy Exchange

The exchange of Powers and Abel was the first of many East-West prisoner exchanges to take place over the next 27 years. It also marked a change in Cold War intelligence. The Soviets had long excelled at espionage, but lost Abel to one of America's early counterintelligence coups in 1957. For their part, the Americans did well at technical collection, and were pioneering the use of overhead reconnaissance from the edge of space and beyond when Powers' U-2 spy plane was shot down.

Francis Gary Powers: U-2 Pilot

Powers had flown for the U.S. Air Force before shifting to the Central Intelligence Agency to become one of the first U-2 pilots in 1956. He flew 27 successful missions in U-2s (not all of them over the Soviet Union) before a surface-to-air missile downed his ship near Sverdlovsk on May 1, 1960.

The Soviets captured him immediately, but took their time telling the news. This made the Eisenhower Administration very uncomfortable because it initially denied that the lost and presumably dead pilot had any intelligence connection. In August 1960, Powers was tried and convicted of espionage against the Soviet Union. He was sentenced to ten years in prison. Powers was cleared by the U.S. government of all allegations of misconduct after his repatriation.

Powers worked for Lockheed as a test pilot from 1963 to 1970. He co-wrote a book about his experience title “Operation Overflight: A Memoir of the U-2 Incident” in 1970. Powers then became a helicopter pilot for a Los Angeles television station. He died in 1977 when his helicopter crashed on his return from covering a news story.

The Man with Many Names

We know far less about the other man on the bridge that February day. "Rudolf Abel" was the name he gave his FBI captors on June 21, 1957. However, he had arrived in the United States in 1948 under the name of “Andrew Kayotis,” and lived in a Brooklyn artists' colony during the late 1940s under yet a third, "Emil Goldfus."

American authorities had no inkling of Abel’s espionage before his deputy defected in May 1957 at the U.S. Embassy in Paris. After Abel’s death in 1971, we learned his real identity: he was William Fisher, an Englishman who had moved to Russia with his family when he was a child.

Abel was fluent in English, German, Yiddish and Polish. He served in the Red Army communications unit, and then worked as a language teacher until 1927. Abel joined the OGPU—the forerunner of the KGB—the same year. During World War II, he served as an intelligence officer on the German front. He was known for his operational tradecraft and survived a lengthy career as a spy before his arrest because he always covered his trail.

We still do not know what he accomplished as a senior KGB "illegal" officer, although he was treated well on his return to Moscow. He was posthumously hailed along with other famous operatives in a commemorative volume published by the Russian foreign intelligence service in 1995.