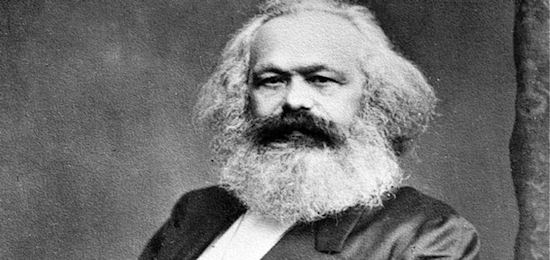

If Karl Marx were to miraculously reappear today, what would he make of the world today?

Firstly, no doubt, he would feel some dismay that despite the advent of space travel, robotics and fibre optic cables, modern medicine has failed to develop an effective cure for carbuncles – an affliction he endured for the better part of his mature years.

But how would he now judge the proclamations he made and the theories he devised so long ago? When Marx was alive, capitalism was established only in a small pocket of Western Europe and the working class was a small fraction of the world's population. He wrote his most famous work, The Communist Manifesto, as a revolutionary wave was sweeping the continent. At that time, he was confident not only that "A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism," but that capitalism could not last:

The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.

Today, capitalism is established across the entire world and the working class is the largest class on the planet. Living standards for those in the West have increased dramatically, and with them, life expectancy. Millions of workers own their own property in the form of houses and have cars, television sets, washing machines, mobile phones and computers. Was Marx's certainty misplaced?

No doubt he might be surprised at just how resilient the system he spent his entire adult life fighting has been; he might also be surprised at the material quality of life that some sections of the working class have achieved. Yet there is also no doubt that Marx would not see the fact of capitalism's continued existence as refutation of his general ideas. Take this striking passage from his masterpiece, Capital:

[Capitalism] establishes an accumulation of misery, corresponding with accumulation of capital. Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole, i.e.,on the side of the class that produces its own product in the form of capital.

Despite some of the more obvious changes in the system, all the talk that it is fundamentally different from the Victorian-era England in which Marx lived is not true. The picture Marx painted above still applies: the richest 5 per cent of the world's population today control 71 per cent of the wealth while the poorest 50 per cent hold barely 1 per cent. In fact, the concentration of wealth in Britain is on track to reach the same Victorian-era extremes of Marx's time by 2030 if current trends continue, according to the High Pay Commission.

The same sort of destitution, the workhouse factories, and the poverty of Marx's time are replicated in countries across the world. And the alienation and social dislocation found in more well-off Western countries would not surprise him at all. He saw that the system cannot fulfil the needs of the majority of humanity. This was only one aspect of his theory of revolution, however.

The certainty that Marx displayed in relation to the coming of a socialist society also rested on the understanding that capitalism produces a conflict between those who produce all the wealth – workers – and those who control that wealth – capitalists.

There is a view today that because Marx argued that each stage of social development – feudalism, capitalism, socialism – comes about as a result of the tensions within the one before, the "evolution" towards socialism will therefore occur automatically, as part of the inevitable march of history, without any need for conscious action.

But for Marx, the decisive element in the struggle for a socialist society was the agency and consciousness of the working class, who are pushed again and again to fight against the inequality they endure and the lack of control they have over the world.

He would have egged on and intervened in the strikes and demonstrations against austerity in Europe and the US today – seeing in them the potential development of an anti-capitalist consciousness necessary for the building of a socialist society. At the same time he would be under no illusion that this consciousness and activity would grow in a linear fashion. Indeed he argued that the "mutual destruction of the contending classes" could occur before the working class overthrew capitalism – a not entirely outlandish prospect in the age of nuclear weapons and climate change.

His understanding that the system produces misery for the majority – and his unflinching confidence in the capacity of the mass of the working class to create socialism – was supplemented by a third factor.

Capitalism is faulty on its own terms. Marx argued that the competitive and expansionist nature of the capitalist world economy means that economic crises are inevitable, take on the most irrational character, and threaten the very viability of the system:

In these crises, there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity – the epidemic of over-production. Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation, had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed; and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce.

The above description, written in 1848, is strikingly confirmed by developments just in the last three years. Just think of the economic situation today: millions of unsold and empty houses in the US, Spain and Ireland while millions sleep rough; massive excess capacity in the world manufacturing sector while unemployment remains stubbornly high across the developed world; a glut of unsold cars, computers and factory machinery sitting idle in warehouses.

The rampant speculation in housing which was the catalyst for the current global financial crisis, the reluctance of businesses to invest lest the returns not prove lucrative enough and the determined efforts by those in charge to force workers to bear the brunt of the crisis through cuts to social spending, lower wages and unemployment were all features of capitalism described by Marx over 150 years ago.

Marx also pointed out that measures to offset crises tend in the longer run to exacerbate them. The current debt crisis facing many of the European governments, a result of their desperate efforts to rescue the banks and other financial institutions in 2008, is one example of this phenomenon.

It is actually this understanding of systemic crisis that grounds Marx's conviction that revolution would come. Just two years after writing the Manifesto, as the revolutionary wave ebbed in Europe, he wrote that "A new revolution will be made possible only as the result of a new crisis, but is just as certain as is the coming of the crisis itself."

This is no simple equation that crisis equals revolution. A crisis does increase the level and intensity of class struggle, as the already existing class antagonisms become sharpened and workers become more aware of their interests and the need to act on them.

For large-scale revolutionary participation to sustain itself, however, major changes in the way people see themselves and the society around them are necessary. Workers need to break with the subservience which is inculcated into them under capitalism and become conscious of their power and ability to organise society themselves. The process of revolution is crucial to this. As Marx wrote:

[R]evolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew.

So today's Arab revolts have their basis in the build-up of frustrations associated with decades of neoliberal economic policies that have impoverished huge sections of the Arab working class and required dictatorial regimes to implement. But their victories are the result of confidence, creativity, courage and determination – not long-suffering silence.

Viewing the scenes in Tahrir Square, the nerve centre of the Egyptian revolution where men and women, Muslims and Christians joined together to overthrown the Mubarak dictatorship, Marx would take great encouragement.

The wave of revolutions in the Arab world, along with the growing movement against austerity across Europe, would represent to Marx a source of hope for a better future and an exciting opportunity to win greater numbers behind the need for the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism everywhere.

One thing we can be certain of is that if he were around today he would repeat himself again and again: "Workers of the world, unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains!"